As technology stands, it is not possible to predict well in advance or with certainty whether, how, where and when eruptions will occur.

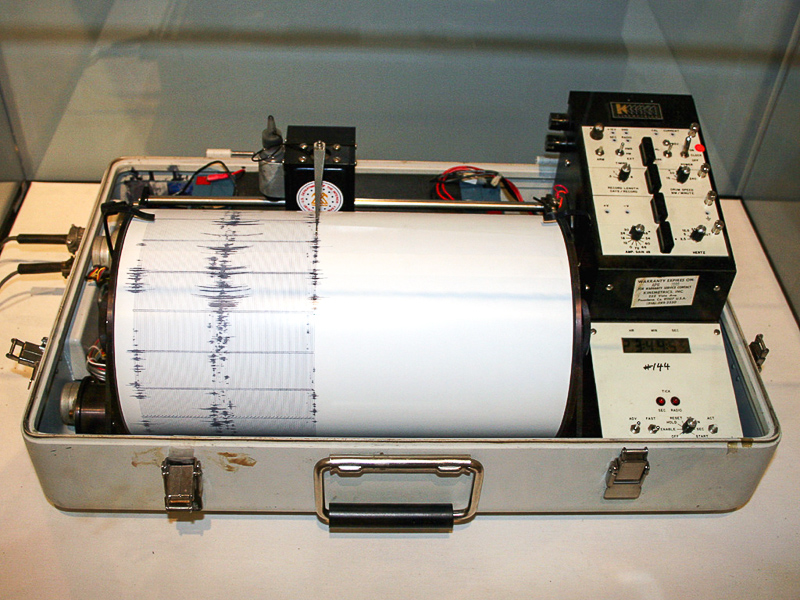

Monitoring in volcanic areas, which in Italy is carried out by the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, is based on interdisciplinary tools and studies including various branches of geology. Nowadays, the lower cost of the “classic”

seismometers

means that dozens of them can be placed at different points of the volcano, joined by instruments that measure the flow of gases emitted by the volcano and their chemical composition.

Other instruments, positioned at strategic points of the volcano, instead measure possible “bulges” in the volcanic structure. In recent years, all these techniques have also been joined by the use of satellites, which can view the expansion or contraction of the volcanic structure with precision and within one centimetre.

The combination of all these techniques and technologies, to which more can be added, combined with statistics from past eruptive events, leads to a rather reliable indication of what the “alert thresholds” of a volcano might be. These thresholds are simply numbers relating to each instrument that, once exceeded, change the alert status from green, which indicates inactivity with normal degassing, to a yellow warning, and to the orange/red of danger and probable eruption. However, there are still no statistics on eruptive cases that would indicate that an eruption will “certainly” occur. There have been a great many cases in the last twenty years where an alert status was reached, but with no eruption.

That is why basic research and volcanic monitoring are still fundamental to understand the dynamics that lead to an eruption, in order to have a clear idea in the near future on how to forewarn of an eruption in a given volcanic system.